Descriptive analysis in statistics refers to an analysis that is not hypothesis-driven. There do not have to be any statistical tests in a descriptive analysis. If you think about making means and percentages – that’s what I mean. It’s usually the most basic thing we learn how to do in statistics.

A lot of people tell me that they are not good at inferential statistics – in fact, they do not even remember when they took it in college. Many people with doctoral-level degrees in a clinical field (such as nursing) do not remember their complex statistics classes from college. The good news is that you do not need to remember inferential statistics to do a good job on a data science portfolio project. You can do descriptive statistics and have a very compelling story to tell.

How to Make a Descriptive Analysis Interesting

You might think that it is pretty boring to take data with premade classifications in it – like year of event – and make percentages of those classifications. If you think that, you are correct – it is totally boring.

It can also be annoying. In a related blog post, I show you how I took a categorical variable that had 77 levels to begin with and reduced them down to 10. If I had kept them at 77, it would have been annoying. Those are too many classifications.

But sometimes, you don’t really have any classifications to go on. Then you have to get creative and add your own classifications to make the analysis interesting. I will demonstrate an example of this using the Black Friday Death Count database.

Black Friday Death Count Database

Just to clarify – in the United States (US), we have a holiday called Thanksgiving that always falls on a Thursday in November. The Friday after Thanksgiving – called Black Friday – is considered the first shopping day before Christmas, which is at the end of December.

The idea is that stores have huge sales on Black Friday. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, when I was young, people used to wake up early and stand in line before the stores opened on Black Friday in order to get the deals before they ran out. Also, people were known to physically fight over scarce merchandise – which is where the Black Friday Death Count database comes in.

I was going down the rabbit hole on YouTube listening to verbal essays about how Black Friday has changed over time (thanks to internet shopping) when I learned about this online database. It isn’t very big, and I don’t know how complete it is. It lists incidents that were reported in the news, and provides links to original articles.

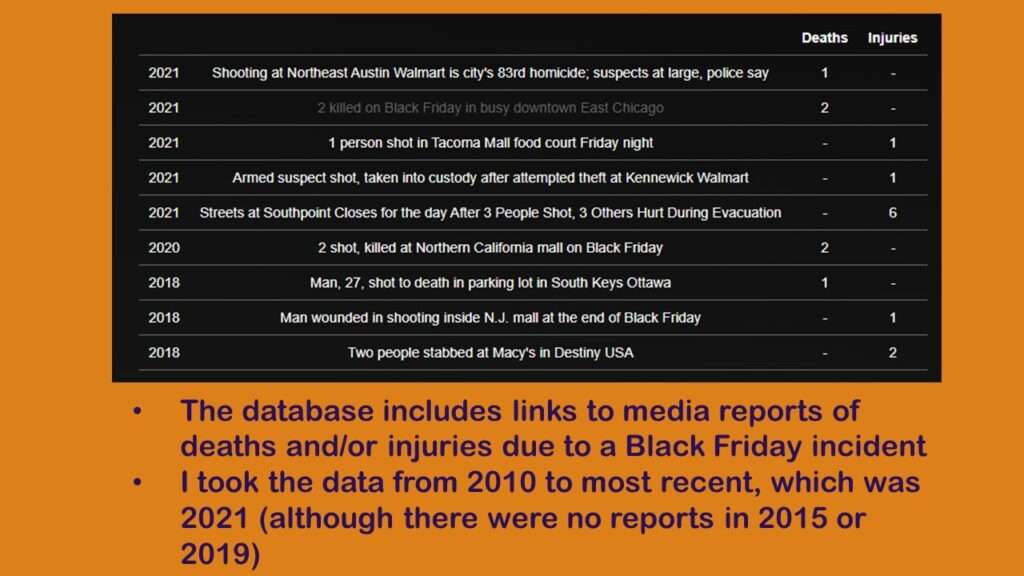

As you can see from the screen shot, the data are short and sweet. I only included reports from 2010 until the most recent report, which was 2021. I use the term “report” because some of the articles reported multiple incidents (including deaths and injuries). Also, it looks like even if there was more than one news outlet that reported it, the database just links to one news report. In total, my analysis was going to include 48 reports.

Data Processing

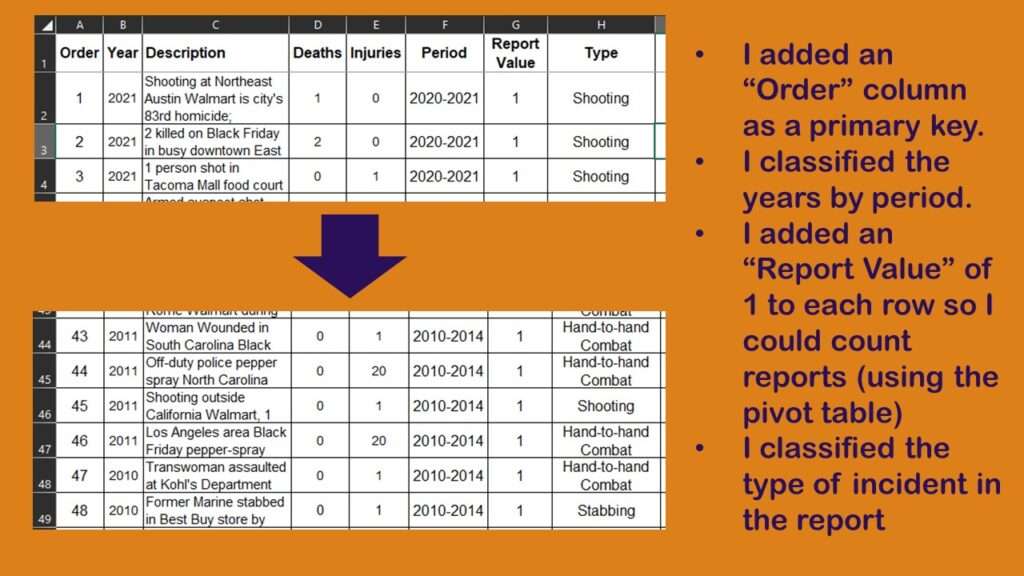

Using Word in a kludgy way, I copied the data from the web page onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet which you can download from GitHub here. I added a column called Order as a primary key (PK), and that’s what I used to count out all 48 reports. I kept the Year, Description, Deaths, and Injuries, and made sure if there were no deaths or injuries, the data said zero.

But as you can see, after looking at the years of the reports, I decided to make a grouping variable called Period. I categorized the reports into three periods: 2010-2014, 2016-2019, and 2020-2021 (the years I skipped were ones without reports). I also wanted to classify each report by type of primary incident (such as shooting, or a stampede, or people brawling over merchandise).

If you read my other blog post about classifying provider types, you’ll recognize my approach here. As I said in that other blog post, I like to use pivot tables in Excel to sum up categories. But in this example – unlike the other example – I do not have a column I want to add up in the native data (since I’m not interested in summing the deaths or the injuries). That’s why I added a column called Report Value and made it say 1 in every row. That is the column I will sum in the pivot table.

Conducting a Creative Descriptive Analysis

Here is where we will see the power of using classifications to kick up a descriptive analysis and make it interesting – even with a small (and possibly incomplete) dataset.

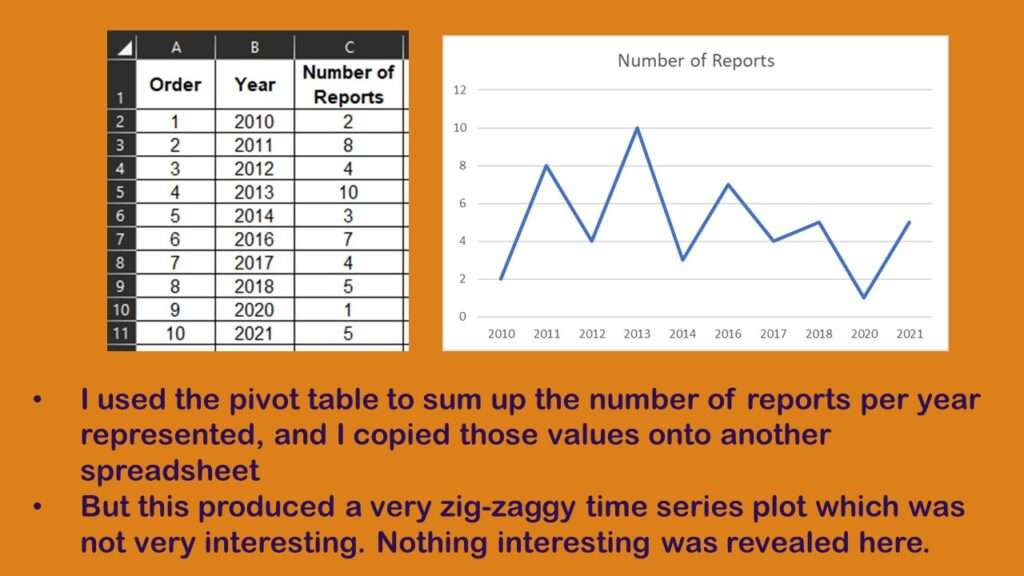

Let’s start by looking at a simple time series analysis by year.

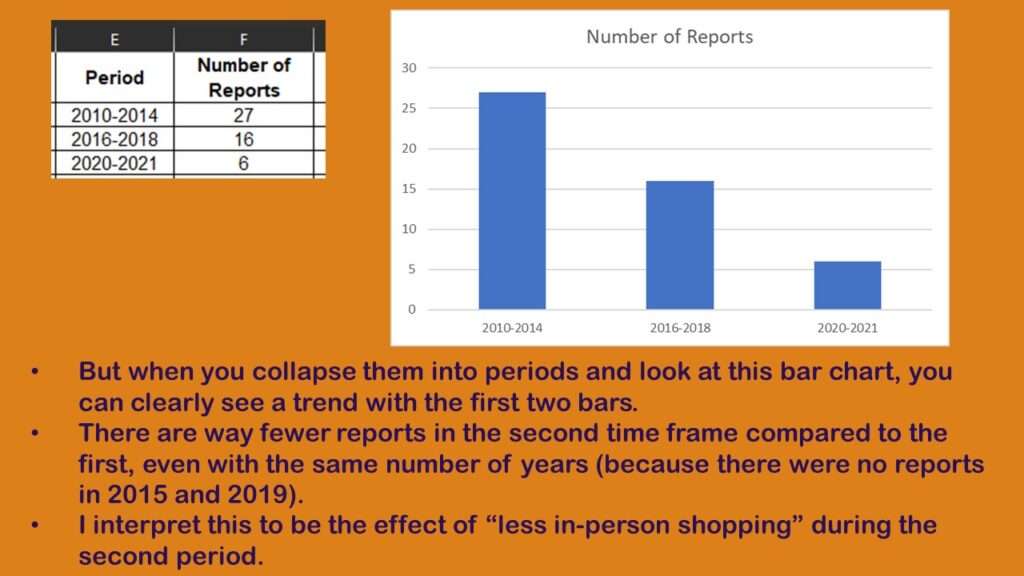

As you can see, the pivot table added everything up well, but the resulting plot looks like the zig zag on Charlie Brown’s shirt, which is not easy to interpret. Now, let’s look at the same data in a bar chart (that is technically a frequency histogram) with the new Period variable across the x-axis.

Admittedly, the third bar – containing just two years, 2020 and 2021 – is not very interesting, because you cannot really compare it fairly to either of the other two bars. But the first two are comparable, and reveal a downward trend. In four years, from 2010 through 2014, there were 27 reports, whereas there were almost half in the next time period, which had only 16 (noting that 2015 and 2019 had zero reports).

Why did it go down so drastically in the second period compared to the first? I think it is because this is a “numerator”, with the “denominator” is number of shoppers, and the denominator went down also. In other words, I don’t think people became less likely to kill or injure each other on Black Friday in the second period. Instead, I think there were a lot more people shopping online than in person in the second period, so therefore, the number of reports of people getting killed or injured went down as well.

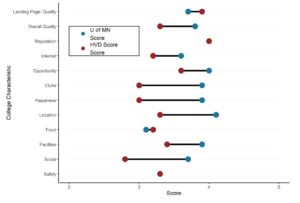

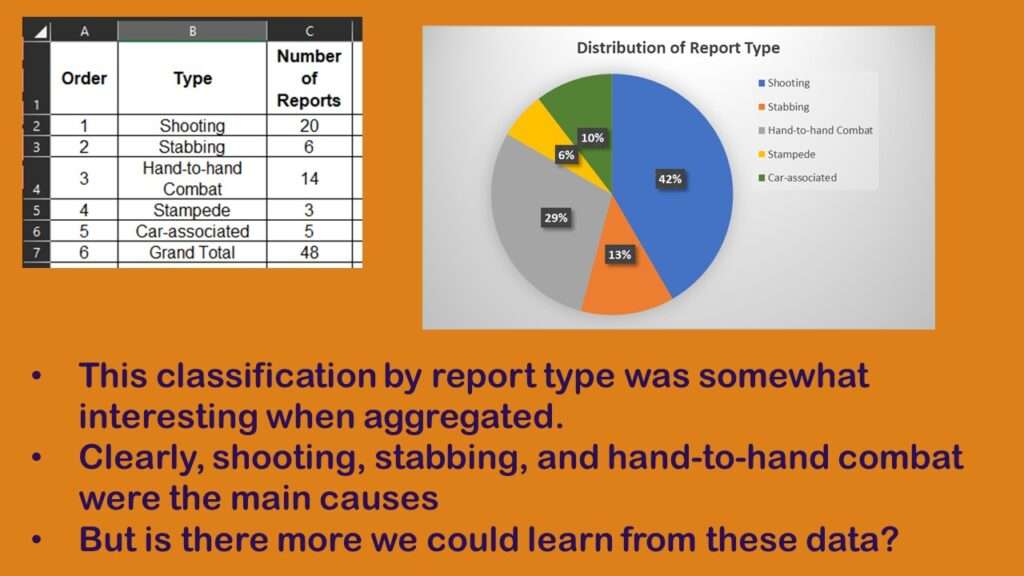

Let’s next look at the distribution of the type of incidents described in the reports.

As you can see, I used the pivot table to sum up the number of reports by type, and I made a pie chart. Almost half the reports were of shootings, and the next two most popular types were stabbing and hand-to-hand combat. But is there more that we can learn from these data?

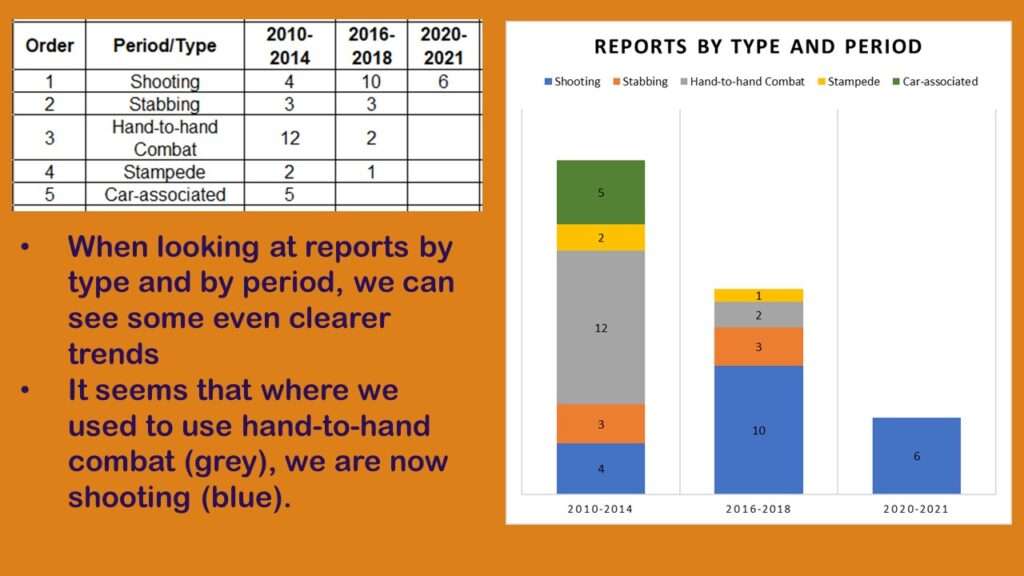

When I turned that earlier histogram into a stacked bar chart by type of report, I saw a pattern. As you can see, as we advance from the first to the third period, the hand-to-hand combat reports go down, and the shooting reports go up. This reflects a background effort in the US to implement policies that promote gun violence and reduce public safety.

So the bad news is that if you are involved in a Black Friday incident today in the US, the likelihood that you’ll be shot is pretty high. The good news is that because there are fewer shoppers out there on Black Friday, the likelihood you will be involved in an incident is much lower today.

Added video January 19, 2024. Updated banners May 8, 2025.

Read all of our data science blog posts!

Descriptive analysis of Black Friday Death Count Database provides an example of how creative classification can make a quick and easy data science portfolio project!